The Sport Too Brutal for the Wild West

Let me tell you a story

Imagine… it’s 1850. You are eight years old, living in the rugged frontier of California.

You wake up early, put on your best clothes, and pile into the wagon with your family for Sunday church. The wooden pews are hard, the preacher’s voice deep and commanding as he talks about sin, redemption, and the path to salvation. But your mind isn’t on the sermon. Your father has extra coins in his pocket today. You saw him slip them in before church. And you know exactly what that means.

After the final hymn is sung, your family doesn’t linger. No polite goodbyes, no idle conversation. Your father walks with purpose, leading you down the dusty road to the wooden arena just outside town.

The air is thick with dust and excitement. The arena isn’t grand—just rough-cut wooden bleachers surrounding a pit, reinforced with split-board fencing and thick logs. The scent of horses, sweat, and something wilder hangs in the air. Your father leaves you and your family in the middle section, where the women and children sit. Then he disappears into the lower stands, where men gather in tight circles, placing bets with hushed voices and firm handshakes.

Your mother presses her lips together. She never liked this. But she doesn’t argue. Not here. Not in front of everyone.

Then, the fighters enter.

The bull comes first—an enormous beast, black as night, its muscles slick with sweat. Its thick, curved horns look sharp enough to pierce through a man’s chest. It stomps, nostrils flaring, eyes rolling wild.

Then comes the bear.

The grizzly is massive—800 pounds of muscle and fury, its coat thick and wild, scars covering its body. It moves with slow, deliberate power, its chains rattling with each step. When it opens its mouth, you see long, yellowed teeth, jagged and deadly.

They are tethered together, forced into confrontation.

A man in a long coat steps forward, raising a pistol into the air.

The whole arena holds its breath. Even the animals seem to sense what’s coming.

*A single gunshot booms

The bull charges first, hooves pounding into the dirt, lowering its head like a battering ram.

The bear barely moves.

At the last moment, it twists, avoiding the full impact. The bull’s horns rake its side, leaving a deep gash, but the grizzly doesn’t flinch. Instead, it lets out a deep, bone-rattling roar and swipes.

The bull screams. You have never heard an animal make such a sound before.

The grizzly’s claws tear through the thick hide of the bull’s shoulder, sending a spray of blood into the dust. The crowd erupts—half cheering, half gasping. The bull bucks, twisting violently, trying to gore the bear, but the grizzly is faster. It lunges, jaws wide, teeth sinking deep into the bull’s neck.

The bull thrashes, kicking up dirt, dragging the bear several feet before the grizzly digs its claws into the ground and holds firm.

Then comes the worst part.

The bear begins to shake its head, wrenching and twisting, blood streaming from the bull’s torn flesh. The bull struggles, its legs giving out beneath it, collapsing in the dust.

For a moment, there is silence. A tense, heavy quiet. Then the bull lets out one last, gurgling breath.

The bear lets go, lifting its head, its muzzle drenched in blood. It licks its chops, savoring the victory, then scans the pit as if expecting another challenger.

The crowd roars. Hats fly into the air, hands shake, money exchanges. Your father grins, triumphant.

You sit there, hands clenched tight, your heart pounding. You want to look away. But you can’t.

You will never forget what you have just seen.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

That was 1850 in California. But how did we get here? Why did men gather to watch such carnage?

The origins go back even further—to Spain and medieval Europe.

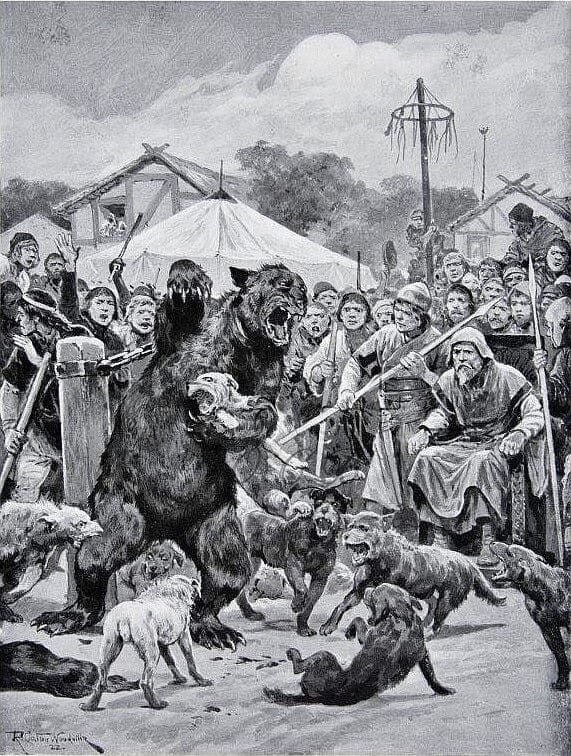

Bear baiting was a popular blood sport in Europe as far back as the 16th century. A chained bear would be set upon by dogs in an arena, fighting for survival while nobles and commoners alike placed bets. When the Spanish came to the Americas, they brought their love of bullfighting. And when these traditions met in California—where grizzlies roamed in the thousands—a new spectacle was born.

Vaqueros—Mexican cowboys—made a game of capturing grizzlies alive. It took four or five men to subdue a bear, using lassos and sheer strength. Some cowboys would ride ahead, provoking the bear to chase them as part of the capture.

The most famous fights took place at places like Whisky Hill near Watsonville, Santa Cruz near Branciforte Creek, and the Castro Adobe. These weren’t underground events—they were community gatherings, a Sunday tradition after church. Women and children sat in the stands while men placed bets below.

Even historians were divided. Hubert Howe Bancroft called these fights “soul-refreshing,” while German botanist Adelbert von Chamisso called them “a vestige of barbarism.”

BULL & BEAR MARKETS

One strange fact? The terms bull market and bear market might have come from these fights.

Wall Street traders say a bull market is when stock prices rise—just like a bull charging upward. A bear market is when prices fall—just like a bear swiping downward to bring down its opponent. Whether the term came directly from these fights is debated, but the imagery remains.

CONCLUSION

By the late 1800s, these fights faded. The grizzlies—once rulers of California’s wilderness—were nearly gone, their numbers decimated by hunting and westward expansion. As new settlers arrived, many saw these brutal spectacles as relics of a wilder past, something that no longer belonged in their vision of civilization. Laws were passed, attitudes shifted, and soon, the sport disappeared. But the hunger for bloodsport didn’t vanish—it just found new arenas. Dog fighting and cockfighting took its place in underground circles, where men still gathered to bet, to cheer, to witness raw competition. And though the great battles of bulls and bears faded into history, their echoes remain—in the language of finance, in the way we watch the rise and fall of champions, and in the undeniable truth that deep down, we still crave the thrill of the fight.